The Global Market of Thalidomide

Thalidomide was developed by German company called Grunenthal and released into market in 1956 under the name “Grippe” for respiratory treatment. Then later on in 1957, researchers at Grunenthal also found out that the drug had inhibitory effect on morning sickness. Hence on October 1957, thalidomide got launched into the market named “Contergan” as a “non-prescription sleeping and tranquilizing agent” (Lenz 1961). Grunenthal's advertisement campaign described Contergan aggressively in Germany as “completely safe” for everybody including pregnant women because it “could not find a high dose enough to kill a rat” ( Russel Morkhiber 1987).

With this idea in mind, the company pushed it in 50 advertisement in major medical journals, 200,000 letters to doctors around the world, 50000 circulars to pharmacists (Russel Morkhiber 1987). Consequently, its sales were comparable to aspirin. Due to its popularity, the drug was exported to other countries: 11 European, 7 African, 17 Asian, 11 North and South America. This soar in popularity was not without opposition. In Germany 1959, Dr Gustav Smaltz ‘s letter denied Grunenthal claim's about the safety of thalidomide. He also had solid evidence to back him up against the safety of thalidomide “To date 20 well known doctor have told our representatives that when they themselves or their patient took one tablet of thalidomide they found themselves still under its effects the next morning, suffering from considerable sickness, and involuntary trembling of hand” (Russel Morkhiber 1987).

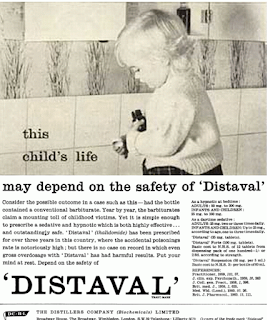

However, Grunenthal still insisting Thalidomide's safety, kept the product in the market. In late 1959, Dr Ralf Voss, a famous nerve specialist, looked into thalidomide and found out that there was a relationship between thalidomide and peripheral neuritis. Voss' statements would go on to be denied by Grunenthal. Voss asserted Grunenthal did “not doubt the validity of my observation but were merely anxious to prevent as far as possible their being made public” (Russel Morkhiber 1959). Despite all of these reports, Distiller Company Chemicals Ltd- a distributor of Grunenthal- still advertised their product as nontoxic and its side effect was absent despite the concern of the company’s development manager. Distiller's advertisements described Distival as "the safe daytime alternative, which is equally safe in hypnotic doses by night." Advertisements also claimed Distival was "highly effective" and "outstandingly safe" in an page titled "the child's life may depend on Distival". (Distillers 1961) It was evident that Distillers had boldly ignored the reports from Voss and Smaltz.

Other advertisements claimed “Distaval can be given with complete safety to pregnant women and nursing mothers without adverse affect on mother or child”, despite no evidence of any studies about pregnancy or relevant animal tests done by Distiller. (Distiller Company Biochemical, 1961) Distillers instead solely relied on Grunenthal’s study without confirming the data. In British Medical Journal, several advertisement cast positive light on Distaval that were made by the company itself from 1959 to 1960 to promote their product. All of these advertisement had the same remark: safe and nontoxic.

The Outcry to Thalidomide

Within 7 years of its release, Grunenthal’s labelling of thalidomide as a safe drug were brought into question. Correlations between Thalidomide and birth defects became clearer in both scientific and public media.

Widukind Lenz, a German Paediatrician, was first to report Thalidomide’s teratogenic effects directly to German authority in 1961. He later in a letter published by the German Paediatric Society in 1962. (Lenz, & Knapp 1962) Lenz suspected the influx in birth defects in German hospitals was correlated with pregnant mothers taking the thalidomide drug. Lenz’s claims were backed up with X-rays of deformed infants, all from Mother’s who had taken thalidomide. This evidence was strong enough for the German Government to remove thalidomide form the German market in late 1961 (Moghe, Ujjwala, Urvashi 2008)

Similar claims and observations came from Australian Physician William McBride who wrote a short letter published in The Lancet medical journal, about thalidomide’s potential teratogenic effects. (McBride 1961) McBride’s findings supported Lenz’s article with statistics including statistical observations that “the incidence of multiple severe abnormalities in babies delivered of women who were given the drug thalidomide during pregnancy… to be almost 20%”. (McBride 1961)

As the scientific community began drawing more attention to thalidomide’s teratogenic effects, the media promptly followed. In 1961, a German newspaper, Welt am Sonntag, published the details of Lenz’s report under the headline: “Malformations from tablets – alarming suspicion of physician’s globally distributed drug”. (Daemmrich 2002). The article drew attention specific quote by Lenz that stated “Every month’s delay in clarification means that fifty to one hundred horribly mutilated children will be born.” (Lenz, & Kapp 1962)

Grunenthal rejected the claims of the Welt Am Sonntag article. Even as Grunenthal withdrew thalidomide from Germany, the company insisted to other countries that it was only due to the “sensationalism of the Welt am Sonntag story” and remained in favour of the drug’s distribution. (Stephen’s 2001). Grunenthal did eventually give in to public and scientific pressures and removed thalidomide from the market in 1961. (Lenz 1988)

In the subsequent legal battles for compensation, Grunenthal’s executives argued that lengthy court proceedings were holding up out of court settlements. (Braithwaite 2013) Executives contended that “If we wait to see where the trial gets us, we shall be sitting here in ten years’ time and the children will have nothing.” (Braithwaite 2013) Many media outlets called argued the compensation was inadequate. Barry Longmuir of the Daily Mail published a front-page article headlined “Scandalous! – That’s the expert’s verdict”. (Longmuir 1971) Longmuir’s article pushed victims to not settle for Grunenthal’s offer, describing it as insulting. (Longmuir 1971)

Scandalous front page article from Daily Mail (Flashbak 2014)

Other media outlets calling for compensation include The Sunday Times, which published multiple articles under the banner “Our thalidomide children, a cause for national shame”. The articles described the extent of Thalidomide’s teratogenic effects and argued that Grunenthal’s offers were “grotesquely out of proportion to the injuries suffered”. (“The Sunday Times vs. The United Kingdom,” 2011)

Yet, in 1965, amongst the fallout of the Thalidomide scandal, Jakob Sheskin, an Israeli dermatologist, published a paper on how Thalidomide could treat skin lesions of leprosy. Sheskin treated six patients with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) and noted dramatic relief after four tablets of thalidomide. (Sheskin 1965) As Sheskin published his results at an early stage he stated there was an “obvious importance of corroborating these findings” (Sheskin 1965). Following the removal of thalidomide from the market, Sheskin’s paper was perhaps the first to support a reintroduction of thalidomide with a new purpose.

References

Lenz, W. (1988). A short history of thalidomide embryopathy. Teratology, 38(3), 203-21

Lenz, W., & Knapp, K. (1962). Foetal malformations due to thalidomide. Problems of Birth Defects (pp. 200-206). Springer Netherlands.

Stephens, T. D., & Brynner, R. (2001). Dark remedy: The impact of thalidomide and its revival as a vital medicine. Cambridge, MA; Perseus pub

Widukind Lenz, a German Paediatrician, was first to report Thalidomide’s teratogenic effects directly to German authority in 1961. He later in a letter published by the German Paediatric Society in 1962. (Lenz, & Knapp 1962) Lenz suspected the influx in birth defects in German hospitals was correlated with pregnant mothers taking the thalidomide drug. Lenz’s claims were backed up with X-rays of deformed infants, all from Mother’s who had taken thalidomide. This evidence was strong enough for the German Government to remove thalidomide form the German market in late 1961 (Moghe, Ujjwala, Urvashi 2008)

Similar claims and observations came from Australian Physician William McBride who wrote a short letter published in The Lancet medical journal, about thalidomide’s potential teratogenic effects. (McBride 1961) McBride’s findings supported Lenz’s article with statistics including statistical observations that “the incidence of multiple severe abnormalities in babies delivered of women who were given the drug thalidomide during pregnancy… to be almost 20%”. (McBride 1961)

As the scientific community began drawing more attention to thalidomide’s teratogenic effects, the media promptly followed. In 1961, a German newspaper, Welt am Sonntag, published the details of Lenz’s report under the headline: “Malformations from tablets – alarming suspicion of physician’s globally distributed drug”. (Daemmrich 2002). The article drew attention specific quote by Lenz that stated “Every month’s delay in clarification means that fifty to one hundred horribly mutilated children will be born.” (Lenz, & Kapp 1962)

Grunenthal rejected the claims of the Welt Am Sonntag article. Even as Grunenthal withdrew thalidomide from Germany, the company insisted to other countries that it was only due to the “sensationalism of the Welt am Sonntag story” and remained in favour of the drug’s distribution. (Stephen’s 2001). Grunenthal did eventually give in to public and scientific pressures and removed thalidomide from the market in 1961. (Lenz 1988)

In the subsequent legal battles for compensation, Grunenthal’s executives argued that lengthy court proceedings were holding up out of court settlements. (Braithwaite 2013) Executives contended that “If we wait to see where the trial gets us, we shall be sitting here in ten years’ time and the children will have nothing.” (Braithwaite 2013) Many media outlets called argued the compensation was inadequate. Barry Longmuir of the Daily Mail published a front-page article headlined “Scandalous! – That’s the expert’s verdict”. (Longmuir 1971) Longmuir’s article pushed victims to not settle for Grunenthal’s offer, describing it as insulting. (Longmuir 1971)

Scandalous front page article from Daily Mail (Flashbak 2014)

Other media outlets calling for compensation include The Sunday Times, which published multiple articles under the banner “Our thalidomide children, a cause for national shame”. The articles described the extent of Thalidomide’s teratogenic effects and argued that Grunenthal’s offers were “grotesquely out of proportion to the injuries suffered”. (“The Sunday Times vs. The United Kingdom,” 2011)

Yet, in 1965, amongst the fallout of the Thalidomide scandal, Jakob Sheskin, an Israeli dermatologist, published a paper on how Thalidomide could treat skin lesions of leprosy. Sheskin treated six patients with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) and noted dramatic relief after four tablets of thalidomide. (Sheskin 1965) As Sheskin published his results at an early stage he stated there was an “obvious importance of corroborating these findings” (Sheskin 1965). Following the removal of thalidomide from the market, Sheskin’s paper was perhaps the first to support a reintroduction of thalidomide with a new purpose.

The Future of Thalidomide

Although thalidomide showed devastating side

effects in the 1950’s and 60’s, serendipitous discoveries have shown that thalidomide

can be used in the treatment of a number of serious illnesses. These

discoveries lead scientists to try and develop numerous thalidomide analogs,

where the analogues retain the therapeutic benefits of the drug without its

teratogenic liability. However, the goal of a safe thalidomide analog may be

elusive if the therapeutic mechanisms of action and the teratogenic mechanisms

of action are closely related or even identical to that of thalidomide. (Kim & Scialli, 2011)

In 1997, the pharmaceutical company

Celgene, with the support of HIV/AIDS activists, sought FDA permission to

market thalidomide, supposedly for the treatment of leprosy, but in reality, as

an experimental “off-label” treatment. By this time, scientific research into

the possible uses of the drug was proceeding rapidly and the FDA actively

initiated the move to re-launch thalidomide. (Ferber, 2015) This move to re-launch

thalidomide helped scientists to discover and report on whether thalidomide has

any therapeutic benefits in treating other diseases along with comparing it to current

drugs. In a report by Kaplan, the results suggest that thalidomide and its

analogues could be used more extensively in leprosy reactions. (Kaplan, 2000). The

analogues of thalidomide, which inhibit PDE-IV and block production of TNFa but

do not stimulate T cells, may be candidate drugs for the treatment of reversal

reactions. (Kaplan, 2000). Another study showed that thalidomide acted more rapidly

in reducing skin lesions. It was shown that by day 7, only 5% of the patients

presented skin lesions compared to 41% of those taking pentoxifylline. (Sales

et al., 2007). With another case report suggesting that patients who are being

treated with thalidomide and corticosteroids concomitantly for type 2 lepra

reaction may be at risk of deep vein thrombosis, and suggests a possible

mechanism for the thrombosis (Vetrichevvel, Pise, & Thappa, 2008). Although thalidomide can be

seen to benefit those affected by leprosy, scientists are still unsure whether

thalidomide is the best drug for this treatment.

Another illnesses that thalidomide can be

seen to help cure is myeloma. In the

report by Attal et al. (2006), it was found that maintenance treatment of

multiple myeloma with thalidomide after high-dose chemotherapy improves the

response rate, the event-free survival, and the overall survival in patients

with myeloma. Thalidomide produced

remissions in 36% of patients with previously untreated asymptomatic multiple

myeloma, similar to the frequency observed in patients with resistant disease (Weber, 2003). Regardless

of the mechanism, thalidomide-dexamethasone provided a simple, relatively safe,

and remarkably effective primary treatment for nearly three-fourths of patients

with previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. (Weber, 2003)

In a

tumor cell, thalidomide makes a particular protein complex (highlighted in

yellow) disappear. The same mechanism causes serious malformations in unborn

children. (Bassermann, 2016)

Thalidomide remains clinically very useful

yet long-term use is not recommended due to the ability of the drug to cause

peripheral neuropathy, a painful condition that results from damage to the

nerves in the body extremities (Vargesson, 2015). However, there is valid moral

case for thalidomide to be available for serious illnesses, even to women of

childbearing years (Ferber, 2015). This viewpoint in Ferber’s article shows the

ethical concerns regarding thalidomide, and how a patient suffering from a

terminal disease should be allowed to take thalidomide rather then take nothing,

which would ultimately lead to the patient’s death.

References

Albrencth, W., & Kref, K.t (2012)

Germany’s long-standing thalidomide scandal. Retrieved from https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2012/11/thal-n19.html

Attal, M., Harousseau, J.L., Leyvraz, S., Doyen, C. (2006).

Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with

multiple myeloma. Blood, Volume 108 (issue

10), 3289-3294.

Bassermann, F. (2016). Retrieved from

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/06/160617104926.htm

Braithwaite, J.

(2014) Corporate Crime in the

Pharmaceutical Industry. Canberra, Australia: Routledge 2013

Daemmrich, A.

(2002). A tale of two experts: thalidomide and political engagement in the

United States and West Germany. Social

History of Medicine, 15(1),

137-158.

Distillers,. (1961). Thalidomide advertisiement. Retrieved

from https://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/oh-yeah-thalidomide-wheres-your-science-now/

Ferber, S. (December 7, 2015). Could thalidomide happen again?. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/could-thalidomide-happen-again-46813

Flashbak. (2014). Retrieved from http://flashbak.com/1968-in-photos-the-high-court-agrees-meagre-compensation-for-thalidomide-victims-5922/

Kaplan, G. (2000). Potential of thalidomide and thalidomide

analogues as immunomodulatory drugs in leprosy and leprosy reactions. Leprosy

Review, 71.

Kim, J. & Scialli, A. (2011). Thalidomide: The Tragedy

of Birth Defects and the Effective Treatment of Disease. Toxicological

Sciences, 122(1), 1-6.

Lenz, W. (1988). A short history of thalidomide embryopathy. Teratology, 38(3), 203-21

Lenz, W., & Knapp, K. (1962). Foetal malformations due to thalidomide. Problems of Birth Defects (pp. 200-206). Springer Netherlands.

Longmuir, H. (1971,

December 21). Scandalous! – that’s the expert’s verdict. Daily Mail, p. 1.

McBride, W. G. (1961). Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. The Lancet, 278(7216), 1358

McBride, W. G. (1961). Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. The Lancet, 278(7216), 1358

Moghe, Vijay V., Ujjwala Kulkarni, and Urvashi

I. Parmar. "Thalidomide."Bombay Hospital Journal 50.3 (2008): 472-476.

Mokhiber, R. (1987) The tragic

children of thalidomide. Retrieved from http://multinationalmonitor.org/hyper/issues/1987/04/thalidomide.html

Sales, A., Matos, H., Nery, J., Duppre, N., Sampaio, E.,

& Sarno, E. (2007). Double-blind trial of the efficacy of pentoxifylline vs

thalidomide for the treatment of type II reaction in leprosy. Braz J Med

Biol Res, 40(2), 243-248.

Sheskin, J. (1965).

Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reactions. Clinical Pharmacology &

Therapeutics, 6(3),

303-306

Stephens, T. D., & Brynner, R. (2001). Dark remedy: The impact of thalidomide and its revival as a vital medicine. Cambridge, MA; Perseus pub

The Sunday Times v

United Kingdom. (2015). Retrieved from https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/the-sunday-times-v-united-kingdom/

Vargesson, N. (December 11, 2015). Thalidomide: the drug with a dark side but an enigmatic future. Retrieved

from http://theconversation.com/thalidomide-the-drug-with-a-dark-side-but-an-enigmatic-future-50330

VETRICHEVVEL, T., PISE, G., & THAPPA, D. (2008). A case

report of venous thrombosis in a leprosy patient treated with corticosteroid

and thalidomide. Jawaharlal Institute Of Postgraduate Medical Education And

Research (JIPMER), 79, 193–195.

Warren, R. (1999) The many faces of

thalidomide (from 1957-1966). Retrieved from http://www.thalidomide.ca/many-faces-of-thalidomide/

Weber, D. (2003). Thalidomide Alone or With Dexamethasone for

Previously Untreated Multiple Myeloma. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 21(1),

16-19.

No comments:

Post a Comment